Cell and Gene Therapy: The Next Frontier in Healthcare

Executive Summary

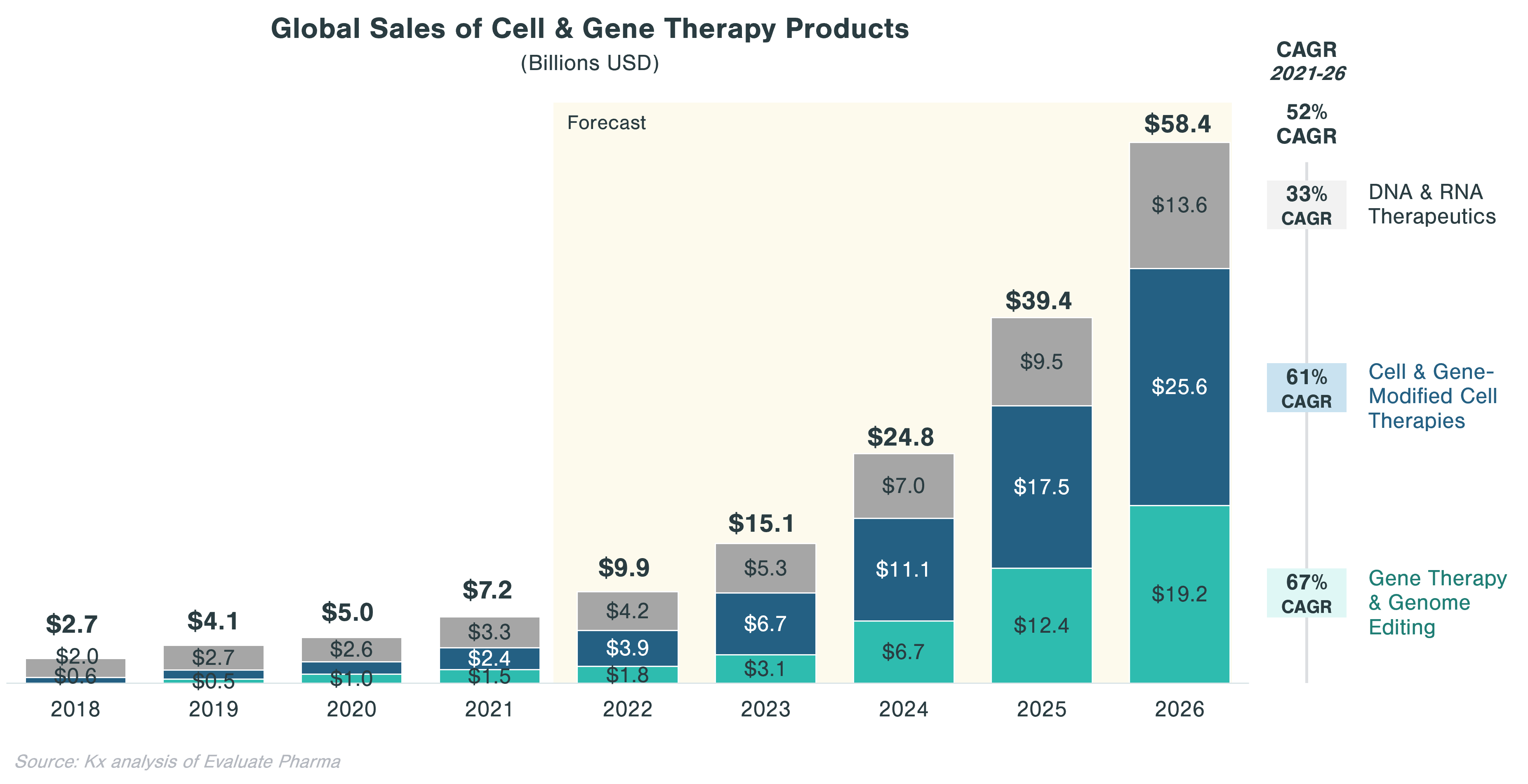

- Cell and gene therapies (CGTs) have become one of the most promising technology categories in biopharma with the global market expected to grow from ~$7B in 2021 to ~$58B in 2026

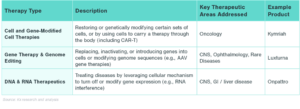

- CGT treatments are broad and can be categorized into three technology approaches: 1) Cell & gene-modified cell therapies, 2) Gene therapy & genome editing, and 3) DNA & RNA therapeutics

- The main drivers of anticipated growth of the sector are CAR-T and cell therapies in oncology as well as gene therapies targeting rare diseases

- CGT development has accelerated with M&A and licensing deals, which have been strong over the last 5 years, in particular after FDA approvals of Luxturna and Kymriah in 2017

- Despite significant optimism, CGT has faced a number of commercial, clinical, and regulatory hurdles that have dampened expectations in the last year

Introduction

Cell and Gene Therapy (CGT) is one of the most promising new frontiers in advanced therapies with the potential for transformational disease-modifying outcomes. As an example, Luxturna, approved by the FDA in 2017, can restore vision in children and young adults with a rare disease that would otherwise lead to blindness. The promise of CGT is potentially very broad, holding hope for treating or even reversing many currently uncurable and more common genetic diseases like hemophilia A or Parkinson’s.

Current State of Cell & Gene Therapy

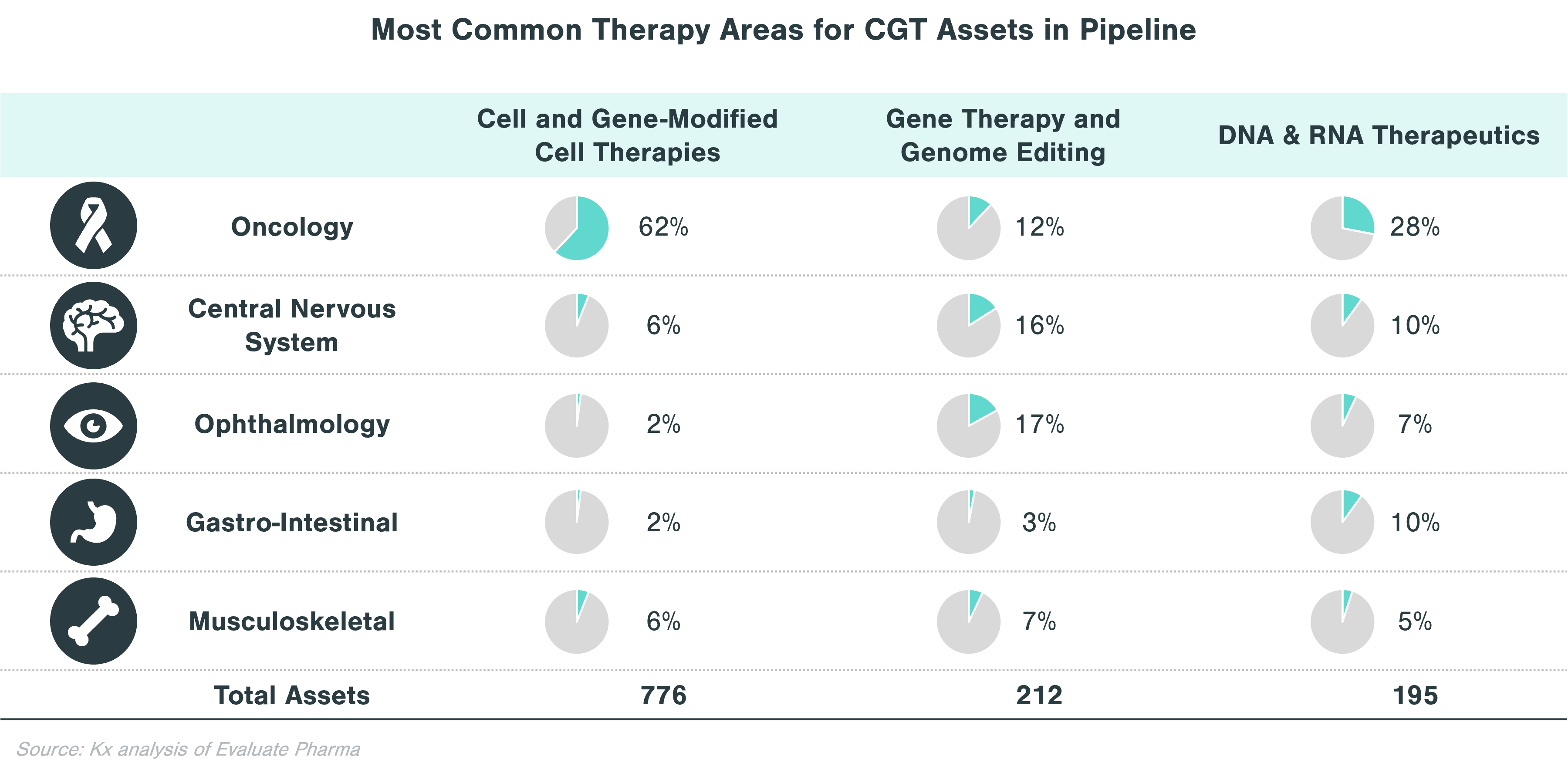

Although the space is constantly expanding in breadth and application, CGTs can be grouped into three broad types of technologies: cell and gene-modified cell therapies, gene therapy and genome editing, and DNA and RNA therapeutics.

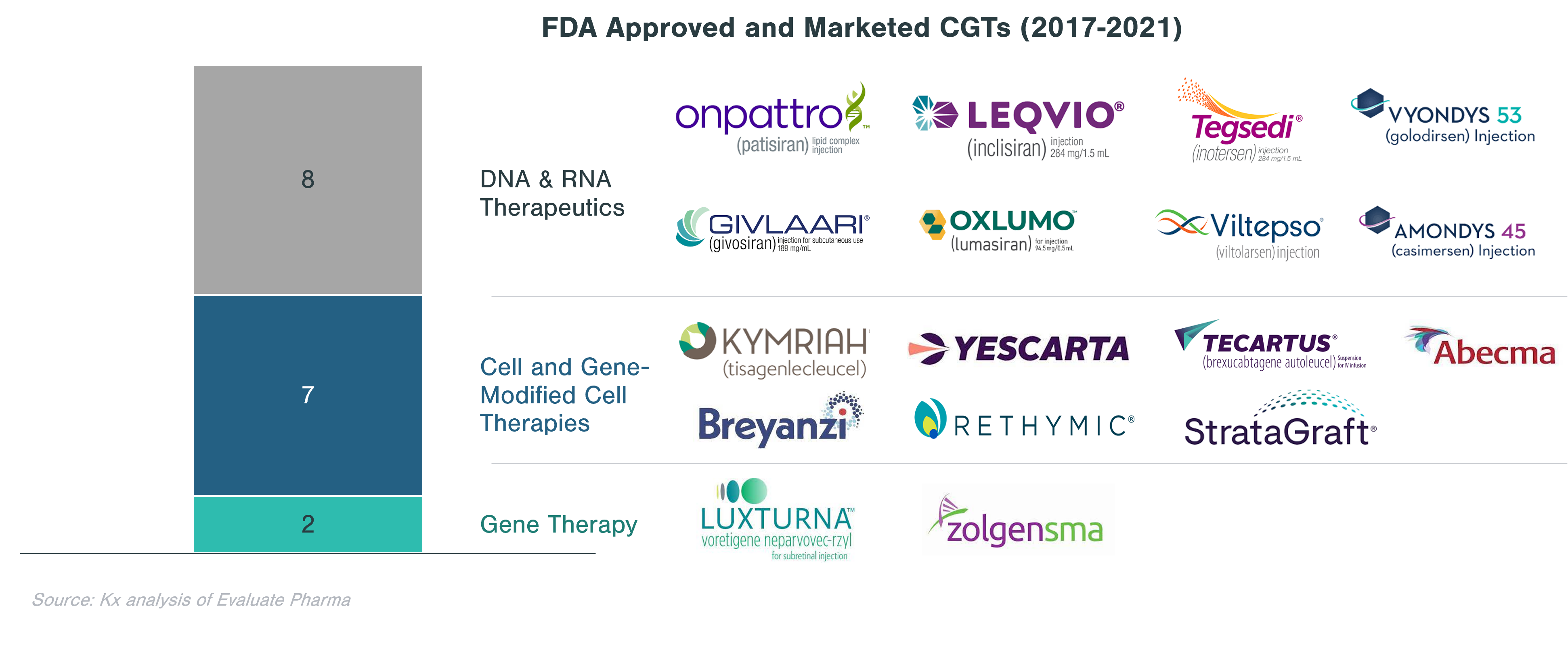

The first CGT was approved by the FDA in 2017 (Kymriah ‒ developed by Novartis and indicated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma). Since then, only 17 CGTs have launched in the US through 2021.

Despite a relatively low market size of $7B in 2021, CGT is forecast to grow to a market size of $58B by 2026 at a 52% CAGR, compared to only 5% for small molecules and 1% for non-CGT biologics (incl. vaccines) markets. This forecast is underpinned by a growing interest in CGT with total financing in regenerative medicine doubling from ~$10 billion in 2019 to ~$20 billion in 2020, according to the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine.[i] Interest stems from Big Pharma as well as from private equity and venture capital. In 2020, 16 out of 20 largest biopharma manufacturers had CGT products in their portfolio, although CGT account for more than 20% of pipeline assets for 2 of the 16 manufacturers.[ii] Out of all private investment made in life sciences, roughly a third is directed toward CGT ($68 billion in 2021).[iii]

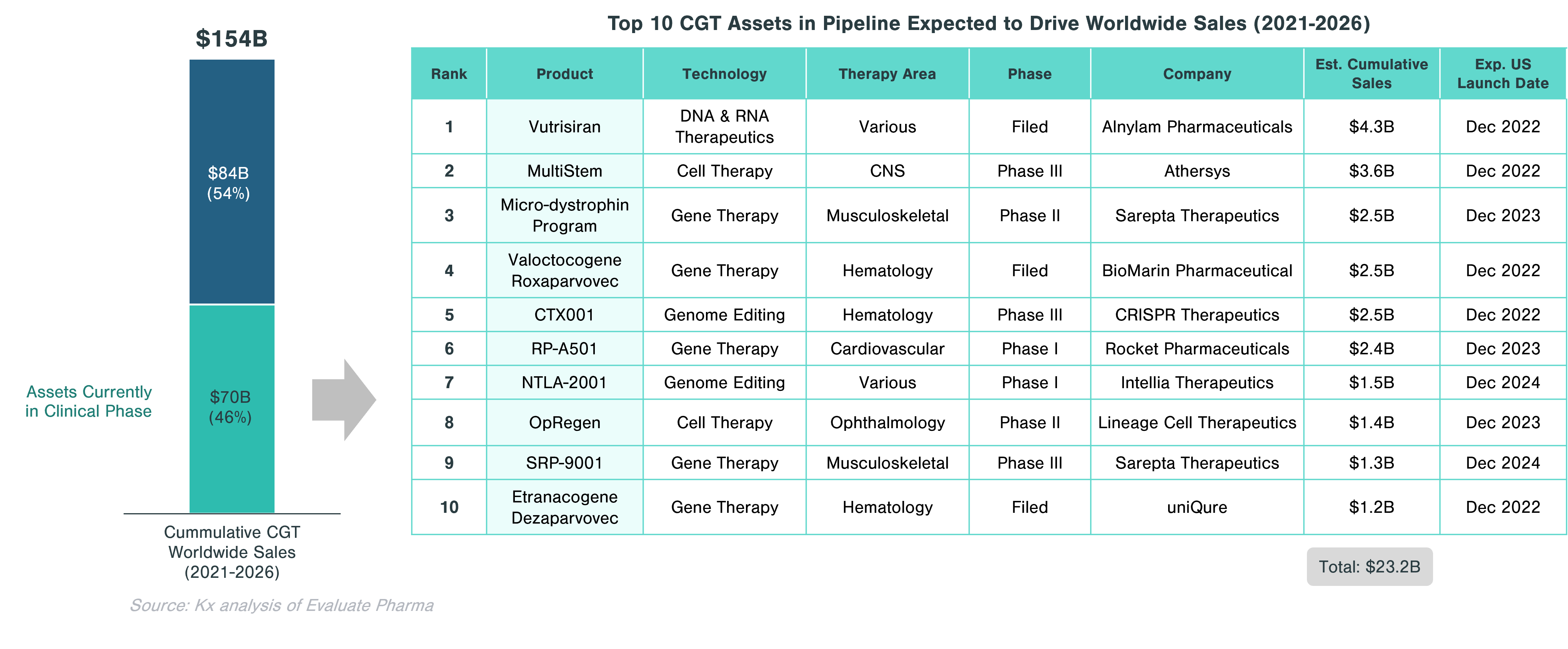

Approximately 46% of the cumulative worldwide sales in CGT ($70.5 billion) is expected to come from assets currently in clinical trials. Significant growth in this segment is expected to be driven by gene therapies, which account for half of the top 10 assets with the highest projected sales. These include Valoctocogene Roxaparvovec (valrox) by BioMarin and Etranacogene Dezaparvovec by uniQure, targeting Hemophilia A and B, respectively.

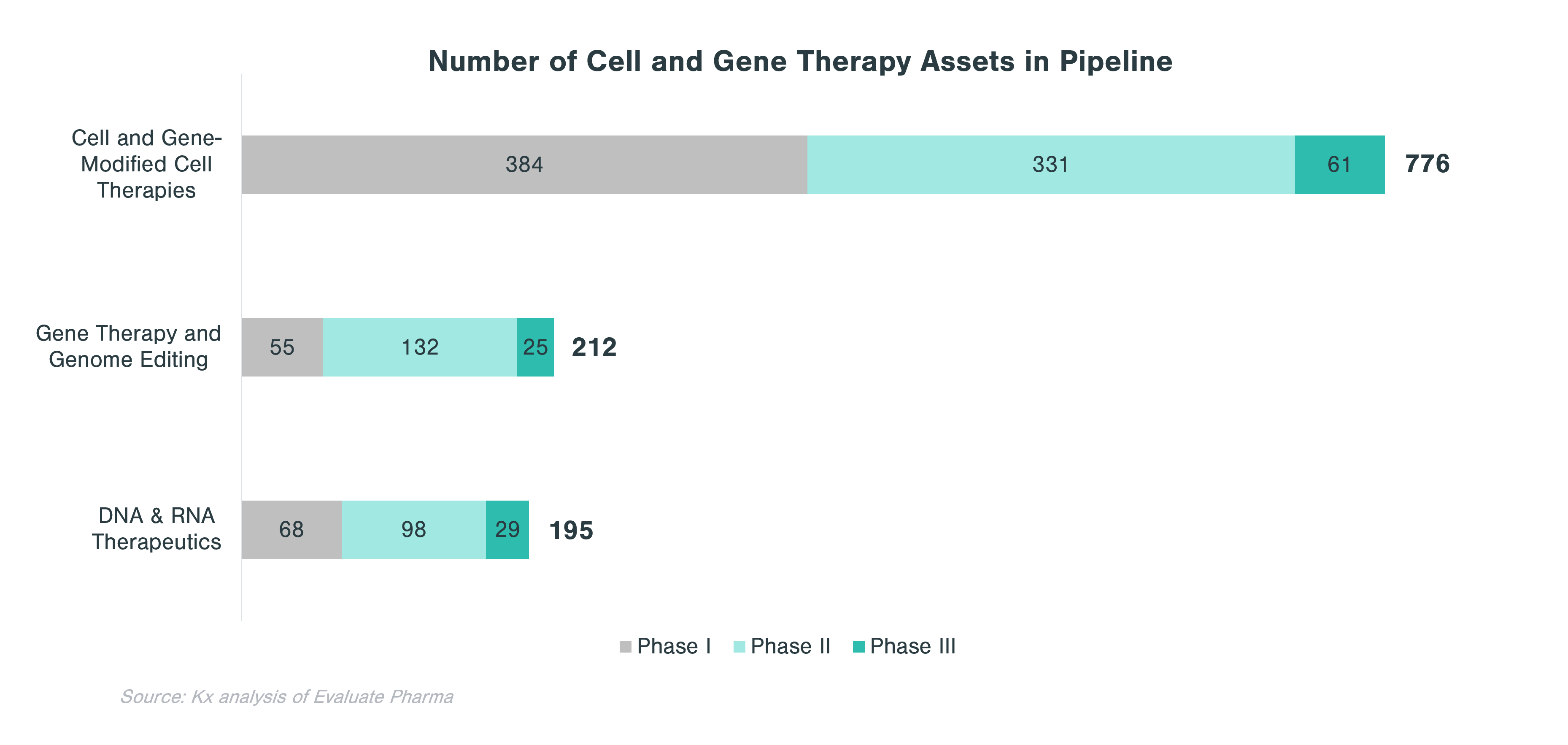

Overall, CGTs have accounted for just over 14% of the 63 biologics approved and marketed in the US in 2020 and 2021. In 2021, out of 130 conventional drugs and biologics approved by the FDA, only 6 were CGTs. However, the clinical-stage pipeline is very strong with 1,183 assets across all three clinical phases. Cell therapies and gene-modified cell therapies (incl. CAR-T) account for almost two thirds of the pipeline.

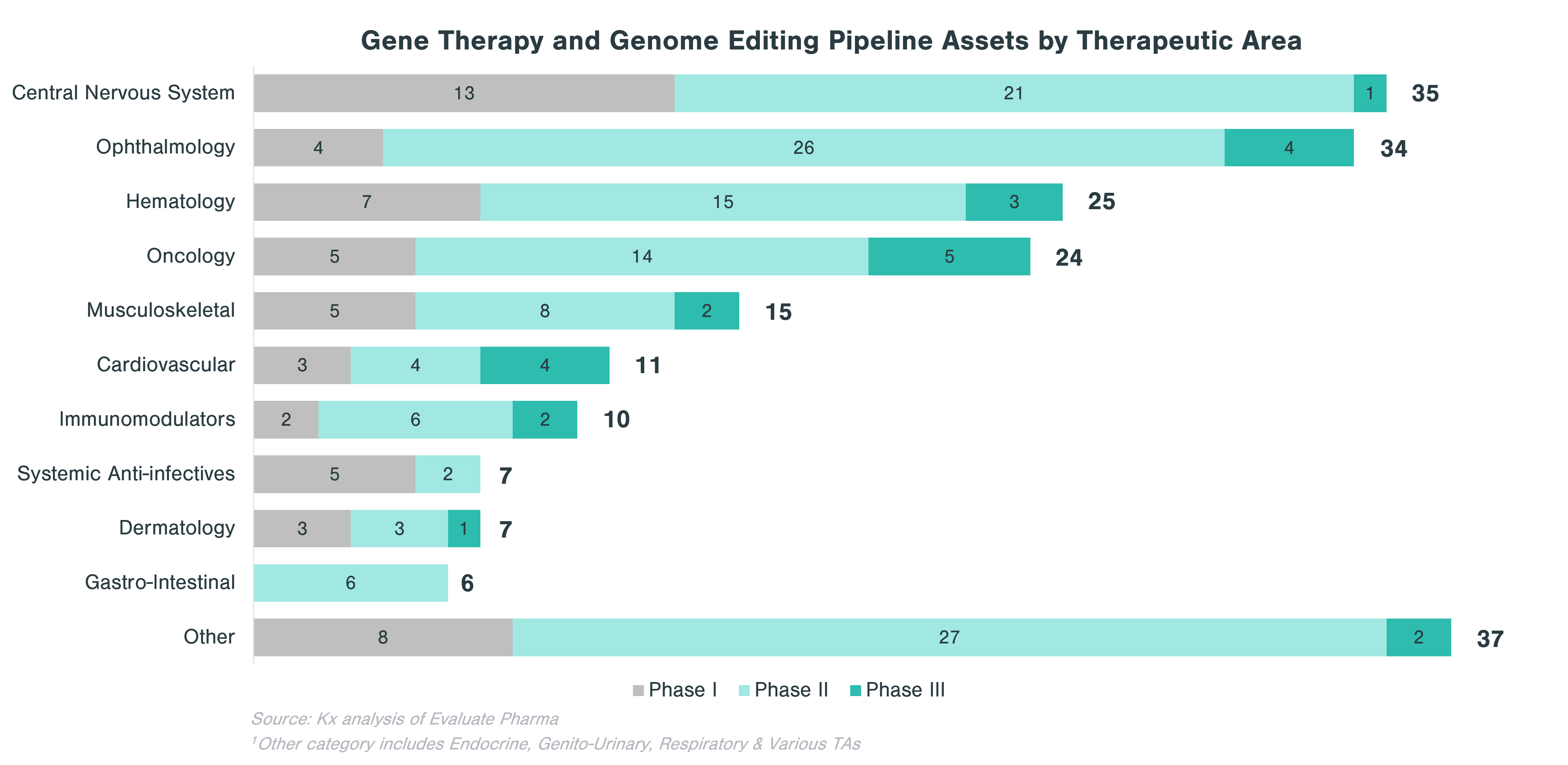

In evaluating CGT assets in the pipeline, there are clear patterns that emerge with respect to therapeutic areas with more substantial investment within each technology category. Cell and gene-modified cell therapy assets predominantly focus on oncology (62% of all clinical stage programs), while assets from gene therapy and genome editing, in addition to oncology, concentrate on central nervous system (CNS) and ophthalmology applications. Over a quarter of DNA and RNA therapeutics in the pipeline focus on oncology and ~10% each target CNS and GI indications.

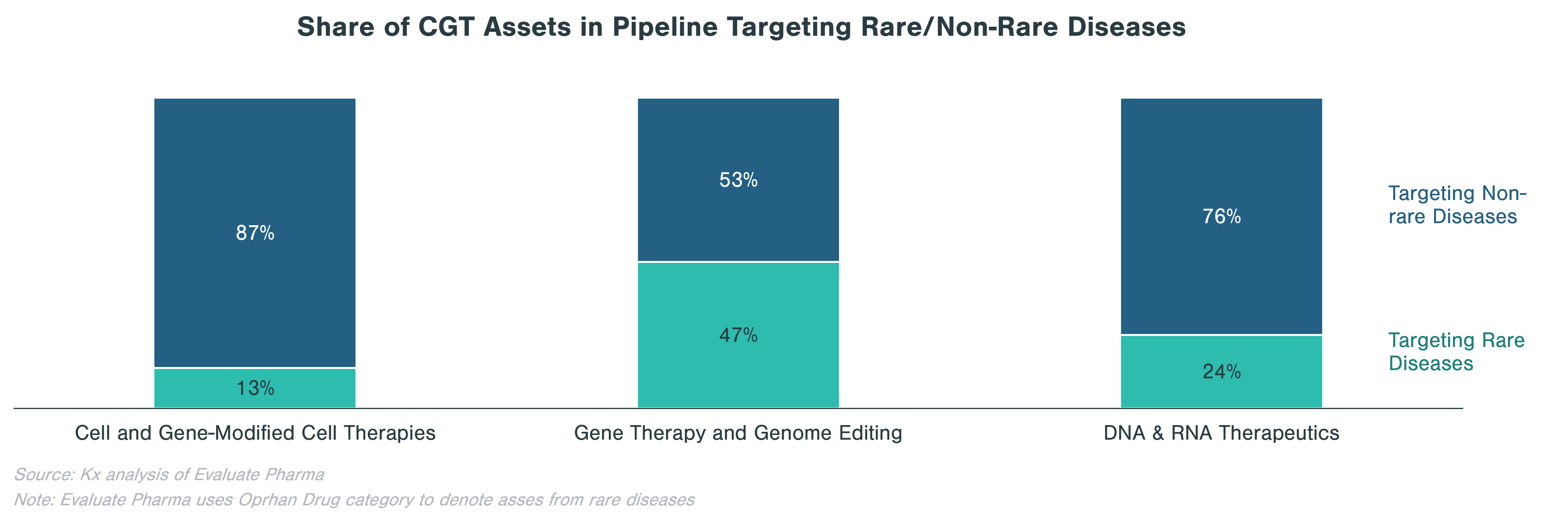

Rare diseases make up a significant portion of clinical stage programs, in particular for gene therapy and genome editing. Almost half of gene therapy and genome editing assets in the pipeline are targeting rare diseases, while cell and gene-modified therapies focus on non-rare diseases, many of which are in oncology.

Pipeline Category Spotlight: Gene Therapy & Genome Editing

Within CGT, gene therapy and genome editing is highly diverse, as biopharma companies are pursuing a range of therapeutic area applications. The goal of gene therapy is to treat a disease by either replacing, inactivating or including new genes into cells, either inside (in vivo) or outside patient’s body (ex vivo). This process is conducted using vectors, of which viruses are the most popular form (e.g., adenovirus, adeno-associated virus, lentivirus and retrovirus). Currently, there are only two FDA-approved gene therapies (Zolgensma and Luxturna). These two gene therapies target rare diseases, but as popularity of the technology grows, it is expected that gene therapy will be used to address more common conditions such as hemophilia A or stubbornly high LDL cholesterol.

Recent Challenges

Despite significant optimism and investment, CGTs have faced substantial hurdles to approval and access, in particular for treatments with long-term or potentially lifetime efficacy. While the effects of RNA interference are transient, gene therapy treatments and gene editing therapies like CRISPR-Cas9 are intended be permanent solutions. This raises the bar for long-term data – both for regulators seeking extended safety data for approvals and payers seeking validation of long-term efficacy to justify $1-2M+ single treatment pricing.

Bluebird bio received EMA approval for two gene therapies—Zynteglo (severe beta thalassemia) and Skysona (cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy)—but subsequently exited EU operations in 2021 due to difficulties gaining payer reimbursement. Bluebird has also encountered several clinical holds and extended FDA reviews. With these hurdles, bluebird’s future is in doubt as it faces the possibility of running out of cash with its stock trading 98% below its March 2018 peak despite the potential for three gene therapy approvals in the next two years, signaling a more challenging environment than anticipated for the sector moving forward.

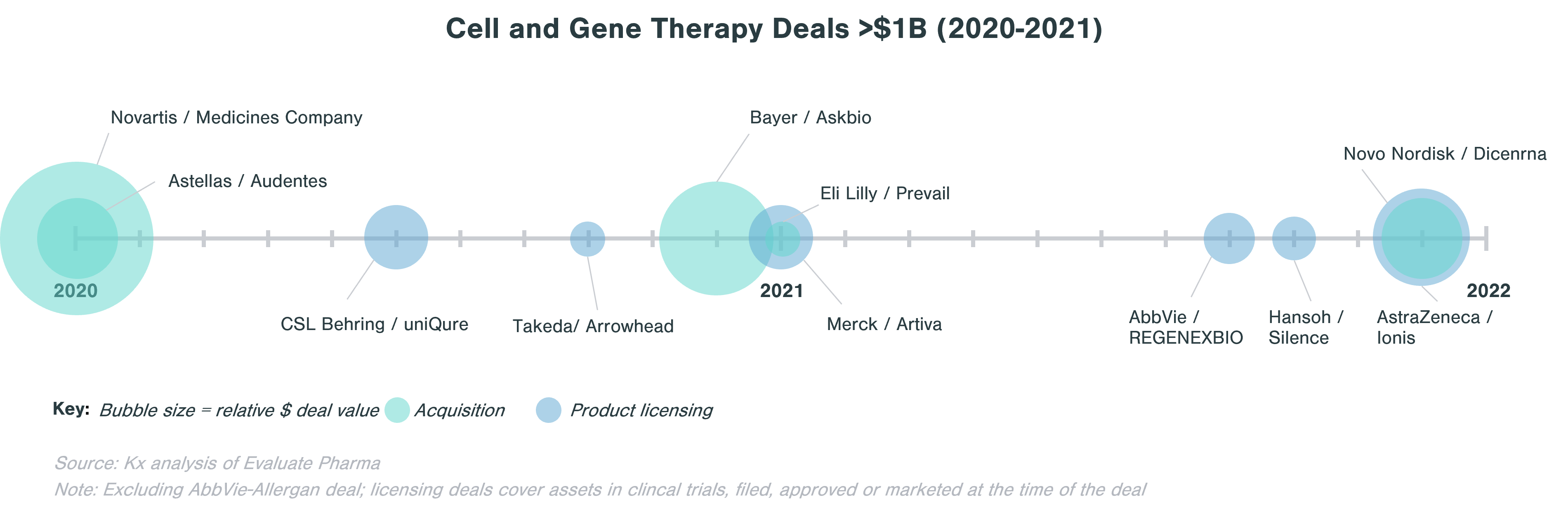

Cell and Gene Therapy Deals Landscape

Only a small portion of launched CGTs originated or were owned by large biopharma companies. Licensing agreements are understandably more common than acquisitions. However, the promise of CGT has led to significant large consolidator interest and investment in pipeline assets.

When looking at deals >$1B in value in the last two years, licensing agreements are about as frequent as M&A.

The deals landscape around CGT has been very active in the last five years as large biopharma companies look to expand capabilities in rare diseases, hematology, immunology, and oncology. Notable deals post-pandemic include Bayer acquisition of Asklepios Biopharmaceuticals (Askbio) in December 2020 for $4B ($2B upfront) to strengthen its emerging gene therapy business through its adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based technology platform and Eli Lilly adding its first gene therapy to its portfolio through the purchase of Prevail Therapeutics in January 2021 for $1B.

When looking for partners, large biopharma often evaluates particular cell and gene therapy technology potential and strategic fit of a target. Companies are often either looking to expand existing CGT capabilities (e.g., Sanofi-Translate Bio deal to strengthen Sanofi’s mRNA center of excellence), to build up a CGT portfolio (e.g., Astellas buying Audentes to develop expertise in AAV), or to access a specific technology platform (e.g. Sumitomo acquisition of Spirovant). Large biopharma is also spreading its bets and investing in early-stage biopharma companies that are looking for ways to make cell and gene therapies address a wider range of diseases, to reduce potential side effects, or to streamline the manufacturing process. One example is Takeda’s collaboration with Code Bio to develop liver-directed gene therapy using lipid nanoparticles (LNP). LNPs are an alternative to virus-based vectors that should not trigger immune response and can carry a larger load than AAV, thus enabling gene therapy to tackle disorders where a larger gene is affected.[1]

Conclusion

These are exciting times for cell and gene therapies. “These concepts are no longer the stuff of science fiction,” noted the former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb. The technologies have potential for breakthrough innovations across a wide range of therapeutic areas and conditions. Some companies choose to engage by developing capabilities in-house, while many others have chosen M&A, licensing agreements, or partnership deals with smaller companies and startups. Given the plethora of investment opportunities and multiple directions in which the CGT space is currently growing, it is even more important for the overall commercial success to choose the right deal partner and the right format for collaboration.

How Kx Can Help

Our experts evaluate business opportunities, deliver top-notch expertise, and make data-driven recommendations to our healthcare clients. Kx can support your growth strategy from opportunity assessments for pipeline investment through commercialization. Contact Sean Vander Linde at sean.vanderlinde@kxadvisors.com to learn more.

References